Is North Carolina ready for the next big one?

Breaking down the “uneven” recovery from Helene, and whether Washington is doing enough to help.

Welcome back to Down from DC, your guide to what’s happening in Washington and how it affects us here in North Carolina. This edition was written by Natalie and edited by Phoebe, with research and editorial support from our team.

If you’re new, you can read more about us here. Please subscribe (it’s free!) and forward to your friends and neighbors.

When Phoebe and I decided to launch this newsletter, we had times like this — when the news out of Washington is very big, and coming fast — in mind.

The sprawling budget and spending bill that President Donald Trump signed into law on July 4 will impact everything from North Carolinians’ finances and healthcare to our immigration enforcement and education programs. Our senior U.S. senator, Thom Tillis, drew an angry rebuke from Trump because he opposed the bill. Tillis responded by announcing he will resign next year, setting up a race for his seat that will put North Carolina at the center of the political universe in the 2026 midterms.

We also started Down From DC because we had questions about the long-term issues facing our state, including many related to the recovery from Hurricane Helene and other climate change impacts. Like, what is the federal government doing to help with the recovery and to prepare for the next big one?

Those questions feel increasingly urgent as we enter the 2025 hurricane season, and there is person I’ve wanted to ask them: Washington Post reporter Brady Dennis.

Brady is one of the best climate and environment journalists in the country. I will admit some bias: I worked in the Post newsroom with Brady for years, and I currently do contract work there. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Brady has won a slew of awards for his work. He is also a North Carolinian who lives in Durham, grew up in Hickory and is a UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus. He and his colleagues reported extensively on the aftermath of Helene, and were Pulitzer finalists for their coverage.

Brady and I chatted over email last week about what disaster preparedness and recovery could look like here in 2025. Then, we got a view of how it is playing out, with deadly floods in Texas and here in our state. The Texas floods have already prompted questions about how and why the warning system failed so many communities. Brady was already in Texas reporting on that story when flooding overwhelmed some communities closer to his home in the Triangle.

Our email conversation from last week is below. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Natalie: Can you start by telling readers about your Helene reporting journey?

Brady: I had traveled to Florida to cover Hurricane Helene’s landfall. On the morning the storm arrived, I was in Cedar Key, Fla., but was paying close attention to the dire weather service warnings coming from western North Carolina. I got a few texts from friends in the mountains about the flooding — and soon also realized other friends had become impossible to reach.

I couldn’t shake the feeling that I needed to get back to North Carolina as quickly as possible, and just started driving north. I made a stop at a friend’s house near Atlanta to sleep, then headed toward Asheville the next morning. The days after are sort of a blur. I made my way to a new place each day — first Swannanoa, then Chimney Rock, and on and on — trying to document the depth of destruction in each spot, even as it was difficult to put into words. With cell service and internet mostly down, and so many roads impassable, I kept driving back toward South Carolina to file stories and call editors.

I have continued to return to western North Carolina in the weeks and months since the storm to witness the recovery — and in some cases, the lack of recovery. We’ve spent time with families who lost loved ones, with residents facing eviction in the wake of job loss, with farmers struggling to get back on their feet, with homeowners along one Swannanoa street trying to rebuild their homes and lives. Just recently I was back in Chimney Rock, a town that has made remarkable progress but remained closed off to the world eight months after the storm.

How would you describe the state of the recovery from Helene? What have the White House, federal agencies and Congress done, and what still needs to be done or funded?

It is very much ongoing and uneven. In one sense, so much has been accomplished, and a lot of federal and state money has helped make that happen. Oceans of debris have been hauled away. The N.C. Department of Transportation has repaired and rebuilt hundreds of damaged roads and bridges. Business owners and homeowners have worked relentlessly to get back on their feet. Numerous downtown commercial districts are open again and welcoming back tourists.

At the same time, you don’t have to travel far off the beaten path to understand the scars that remain, and that probably will take years to overcome. In some communities, many homes have been demolished, and others are still not livable. Private roads and bridges are in disrepair. Businesses have closed or face precarious futures as they struggle to reopen. Everywhere, there is uncertainty and angst.

That’s not to say there hasn’t been help from the state and federal government. The N.C. Assembly just days ago passed the latest in a string of Helene relief bills, which will send another $500 million to western North Carolina. This spring, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development approved North Carolina’s plan to spend $1.4 billion in federal disaster block grants on Helene recovery, though it will take time for that money to begin to make an impact.

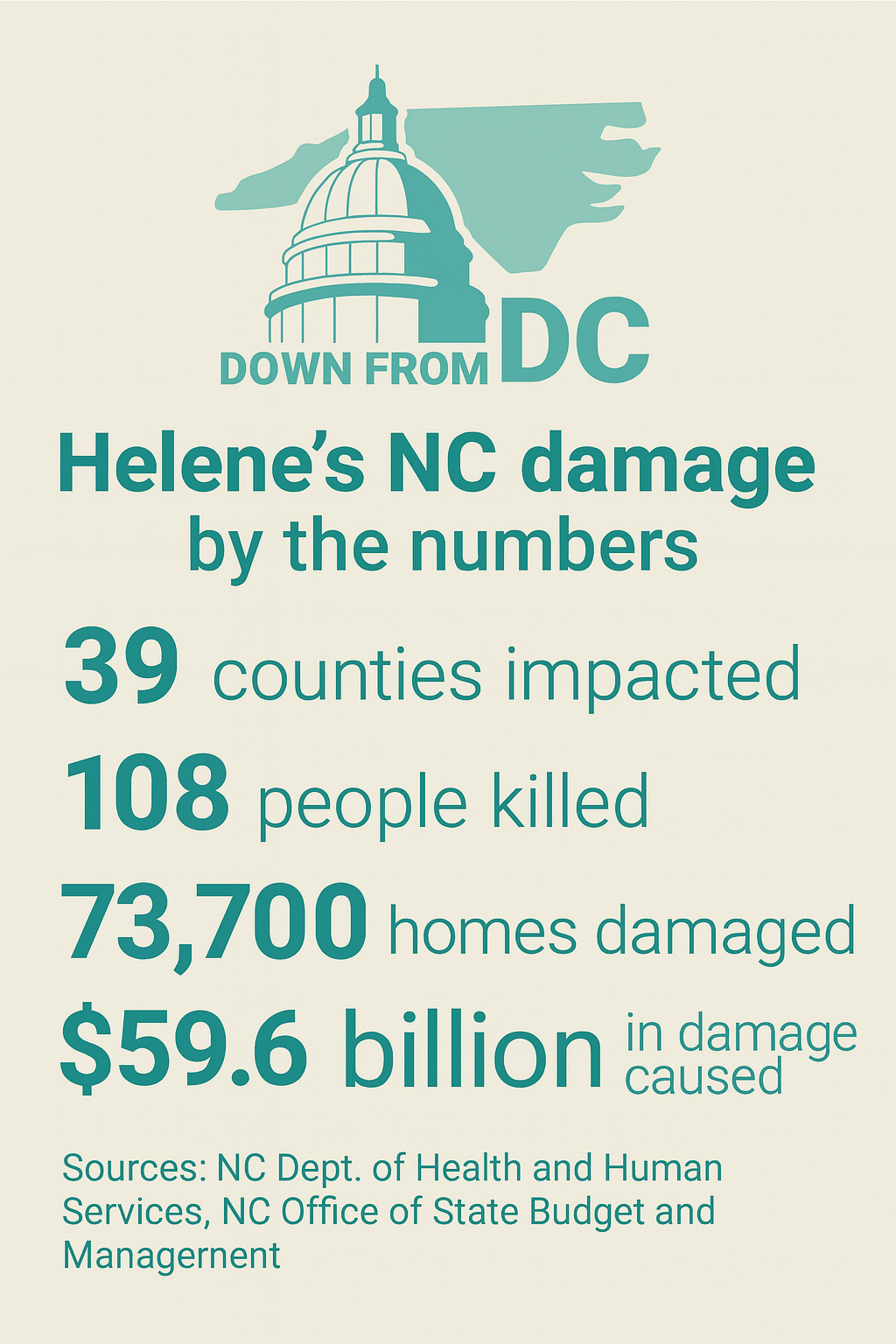

All those are positive developments. But it’s important to remember that Helene is estimated to have caused about $60 billion in damage, so the scale of what is needed is massive. Also, while the government aid is critical, the recovery to this point has also relied massively on a range of nonprofit aid and faith organizations that have done so much of the initial work in the hardest-hit communities. That, plus the ongoing reality of neighbors helping neighbors.

What has changed in terms of North Carolina’s preparedness for a major storm since the 2024 season?

There is a lot of uncertainty on this front. I suspect the residents and public officials in western North Carolina will be more prepared, if only because there is now a recognition that an event as catastrophic as Helene is possible in the mountains.

But as in other states, emergency managers in North Carolina have watched as FEMA has lost significant numbers of staff, and President Trump has talked of doing away with the agency. Will FEMA show up as it has in the past if there is another disaster this year somewhere in North Carolina? That’s an open question. Important agencies such as [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] which includes the National Weather Service, have also faced cuts that have led to questions about whether forecasts will be as timely and detailed.

Outside of western N.C., where else are you seeing the impacts of federal policy in our state?

So many places. For example, the regulation (or rather, deregulation) unfolding at the Environmental Protection Agency could have any number of consequences around the state. How the agency ultimately approaches water quality issues could affect the amount of PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” allowed in the water supply, or how the disposal of coal waste gets regulated. These decisions could impact wetlands and other waterways. Decisions about emissions standards for power plants could affect air quality.

Policy changes at the Interior Department could impact endangered species such as the red wolves at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, or affect where logging is allowed in the mountains, or whether offshore drilling exploration can take place off the Atlantic coastline.

The layoffs and other staffing reductions we have seen taking place at federal agencies already have impacted a number of climate and environmental workers in North Carolina, from staffers at the EPA’s facility in the Research Triangle to NOAA researchers based in Asheville.

Then there are the many academic research grants that have either been cancelled or remain in limbo. I have heard from coastal researchers at multiple N.C. universities who are concerned that the main source of funding for the work they are doing to better understand sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, flooding and other issues could vanish.

How much has climate change affected the state already, and what do you expect in the years to come? How could federal policy affect those impacts?

The changing climate is having profound effects in North Carolina, just as it is in many other places. I have written about a number of these impacts. Last summer, as part of a project on rapidly rising sea levels throughout the Southeast, we focused on Carolina Beach and documented just how often “sunny day” flooding is happening on its streets. Many communities are seeing this so-called nuisance flooding happening more and more, and it is becoming much more than a nuisance.

Rodanthe [on the Outer Banks] is home to some of the most rapid rates of erosion and sea level rise on the East Coast, and houses there keep falling into the sea. Few examples of climate change are as unmistakable as the “ghost forests” proliferating along parts of the Carolina coast, which are a result of saltwater intrusion and are causing a shift in coastal ecosystems.

Climate change also means that North Carolinians, like other Americans, are in for more debilitating heat waves as time goes on. Not to mention more intense, frequent hurricanes and the potential for extreme rainfalls because of increased moisture in the atmosphere.

Federal policy has a significant role to play, both in helping (or not helping) communities prepare for these changes. Federal money is also the main vehicle for getting folks out of harm’s way through approaches such as home buyouts in floodplains or projects to upgrade infrastructure and make communities more resilient in the face of extreme weather. Most flood insurance comes through the federal government. Disaster relief and rebuilding are heavily reliant on federal funding.

So much of that traditional federal role is uncertain in this moment, when President Trump has said he wants states to shoulder more of the burden of disasters. But what is certain is that North Carolina is going to have to grapple with those challenges, one way or another.

You can follow Brady on X or Bluesky, or see his latest work here.

Thank you to Justin Cook for allowing us to feature photos from “Tide and Time,” his 2018 piece on coastal erosion on the Outer Banks. You can see more of his work on his web site, and his wrenching Helene work here.

Read more on Helene recovery:

From Raw Story: Militia fears forced medical team responding to Helene to flee

From NC Newsline: FEMA will stop matching 100% of Helene recovery money in North Carolina

From NC Rabbit Hole: What happened when disaster aid dried up after a big storm hit Asheville

What else is coming down from DC?

Tillis is one of three Republicans in the Senate who voted against the budget bill. In his statement announcing his resignation, he lamented the lack of bipartisanship in Washington and said he’d spend the rest of his term “producing meaningful results without the distraction of raising money” and “having the pure freedom to call the balls and strikes as I see fit.” One way he plans to do that: Opposing any Trump nominees who express support for Jan. 6.

It was the steep cuts to Medicaid in Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” that were the center of Tillis’ opposition to it. The cuts are consequential everywhere — the Congressional Budget Office projected nearly 12 million Americans will lose their health coverage because of them. Here in North Carolina, they stand to force hundreds of thousands of people off health coverage, just two years after the state expanded Medicaid. The Carolina Journal explained how here. The cuts also pose a financial risk to rural hospitals, like one in Martin County that was set to reopen and now may not, the New York Times’ Eduardo Medina reported.

The bill also slashed funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, creating a gap that food assistance program leaders told WUNC’s Abigail Celoria they don’t know how they will address. The Asheville Citizen Times’ Jacob Biba has a good rundown on how those two provisions will impact western North Carolina. DFDC will have lots more about what it means here in our next edition.

Late last month, the Trump administration said it would withhold more than $6 billion in federal grants that had previously been approved for education programs, including for K-12 education and before-and-after school care programs. The administration said it is reviewing funds that were approved under the Biden administration, and that funds will not be released prior to completing the review. The funds include almost $169 million that had been set to go to North Carolina programs. WUNC has a county-by-county breakdown of the funds that are frozen.

The Trump administration is also rolling back a 2001 rule that prevents road construction in federally owned wilderness. The Asheville Watchdog’s Jack Evans reported last month that the move could open 172,000 acres in western N.C. to logging, which could in turn affect water quality and wildlife. Describing the region, Than Axtell, a fly fishing guide, told the Watchdog: “That is our cultural heritage. I don’t understand why there’s such a rush to put roads into every living acre of forest.”

This is deep and insightful reporting not found elsewhere. Here on the NC coast and in the mountains, climate change is real and worsening. We've survived two hurricanes here on the "inner banks" of NC, and each time the surge rises, and the damage increases.

Once again, thanks for giving us the straight story. It's the only antidote in the poisonous waters of lies.